August 02, 2021

How NCPTF Helps Law Enforcement Find Missing Children

.jpg)

Max Bernhard

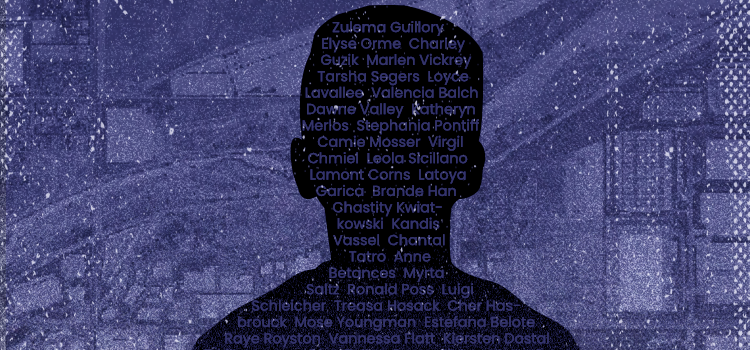

Every year, hundreds of thousands of children are reported missing in the United States. Last year, there were 365,348 reported missing children, the year before 421,394, according to Federal Bureau of Investigation data. Meanwhile, the pandemic has made finding missing children harder for investigators.

Even before the pandemic, crucial resources and technical expertise were often unavailable or not sufficiently funded. The National Child Protection Task Force, or NCPTF, has been trying to fill that gap. The group consists of experts in legal strategy, OSINT, cellular mapping and analysis, dark web, and data exploitation. Together they offer investigative expertise, training, and resources to law enforcement in the US and abroad, working on human trafficking, child exploitation, and missing persons cases.

"Our goal is to unstick law enforcement. If they've got an investigation, we may jump in and say, we're looking at it," says Kevin Metcalf, one of the founders of the group. NCPTF uses facial recognition, geolocation, and an arsenal of other tools to find missing children and identify suspects. They also offer advice on legal processes such as obtaining cell phones and other data.

"If a law enforcement agency comes to us with a case, and they don't know where to go, we will help them get unstuck. We will give them ideas; we'll brainstorm. Sometimes that's all it takes," he says. NCPTF has had more than a thousand case assists in 2021 already, and has recovered over 50 kids and identified more than 50 suspects, he says.

Metcalf spent more than 30 years working in law enforcement and more than 7 as a federal agent before attending law school, becoming a prosecutor, and ultimately starting the NCPTF. "As a prosecutor, you have to be able to take all of the data in an investigation and essentially tell the story that the data tells, and it's got to be reliable," he says. "It's like doing an OSINT investigation; you have all the evidence, you've got all this stuff laid out. And you say, this is how this has to have happened, right?"

As a prosecutor, it can be challenging to explain the technology and the evidence obtained with OSINT methods to jurors. "It's quite a challenge to take legal concepts and apply them to modern technology that is constantly changing," Metcalf says. "After I'd done that several times, in these trials, I'm thinking why are we not doing this on the front end, during investigations?"

Metcalf started teaching techniques, such as investigating cell phone records and assisted in several cases. Further collaborations with more and more people followed. Today, the NCPTF consists of dozens of experts and volunteers who spend hundreds of hours trying to solve and assist in cases.

Piecing together the puzzle

Metcalf says technology like facial recognition software or cellular data can help speed up investigations but that by itself, this data is insufficient. "You can't take action based on an algorithm telling you something; you can't take action just because you have a device that is in a certain area at a certain time," he says. "I need that witness saying 'I saw this vehicle and I saw the guy matching this description coming out of an apartment,' you combine that with the cell tower data, putting that phone there, you know, now you've got a little bit more." Ultimately all the gathered evidence has to fit together and form one cohesive scenario, he says.

Metcalf says NCPTF's core group consists of investigators and prosecutors who are familiar with the legal process and people highly skilled in open-source intelligence. The team includes experts in geolocation, such as Bellingcat contributor Carlos Gonzales, and people familiar with cryptocurrencies and the dark web, for example. "So we have that fusion of law enforcement with OSINT, and then we also have access to a lot of tools like Skopenow that really enhance what we do and speed up what we do," he says.

"We take the investigators through the entire process until they say, oh, I've got it, I can take it from here. [...] So that's kind of the flow of what we do. We help them to the point where they can either take it on their own or where a child is recovered, or a predator is identified," Metcalf says. "Sometimes that's the last we'll hear because [law enforcement] will work the case, they'll find the kids, they'll find the predator, they'll achieve their goal."

Finding pivot points

"The first thing that we do at the outset of every case is take stock of what we have to start with. [...] The tiniest little detail can take you off onto a rabbit hunt for hours," says Griffin, an NCPTF investigator who goes by @hatless1der on Twitter. "In a worst-case scenario, we start with a missing child and maybe a picture of them, and that's it," he says. In the best case, law enforcement is already heavily involved and has collected data from the child's devices or found its social media accounts, he adds. "You kind of have to take stock of everything first and gameplan your approach."

After identifying the available evidence, the group sets its targets for the investigation. "It all depends on whatever the initial case evidence is. The goals might be as simple as finding this person on social media, identifying any recent activity, looking for contacts, things like that. Or it could be very specific, especially if the case involves a suspect," he says. "You never know what direction you're going to go off into because of the person's interests, or their online presence, or their lack of an online presence. So there's really no one size fits all approach to it."

Nevertheless, there is usually at least one of three essential starting blocks available: an email address, a phone number, or a username, Griffin says. "Even if the child is missing, the reporting party is probably going to have at least one of those things."

Another crucial aspect is flexibility which is part of the reason why NCPTF has been trying to diversify its ranks over the past year, Griffin says. “We tried to focus on bringing in people that are geographically diverse, of a diverse background, people that bring different diverse perspectives because that makes us more effective as a whole.”

Taking the same regimented approach to everything can slow down investigations, he says. “When it comes to a missing child, some cases are solved in a couple of hours, some a couple of days, some go on for years, unfortunately, but you have to be super flexible and adaptable. [...] And time is always of the essence.”

In the end, the most important success factor is teamwork, he says. "There's no ego, everybody is literally in the moment, fighting for the same cause, for the same person, the same victim, and just trying to make it happen no matter what."